Seeing the problem. The juvenile justice system in the United States is intended to reduce crime and increase public safety while holding youth accountable for their actions. However, for the last three decades the system has focused more on punishing young people, processing them in the formal court system, and confining youth in large, prison-like facilities, sometimes with adults, at an annual per-youth cost of $149,000.1

Data on public safety outcomes has shown that the use of harsh punishment, such as incarceration, has not been effective in supporting youth rehabilitation, education, or development. In actuality, punishing youth by confining them to large institutions has had a “criminogenic” effect. In such institutions, incarcerated youth do not have access to adequate educational services, social service supports, or mental health treatment—resulting in decreased graduation and employment rates—and criminal records reduce their chances of a successful transition into adulthood. Youth who are confined with adults are also vulnerable to physical and sexual abuse, days or months spent in solitary confinement, and exposure to the influence of adult criminals.2

Understanding the problem. Because of the complexity of the juvenile justice system, reform is not a quick fix or simple set of technical solutions. In the United States, the juvenile justice system operates primarily at the state and local levels, with relatively less federal funding, oversight, or control. The system involves many different players and sectors including school security personnel, local law enforcement officers, district attorneys, juvenile public defenders, juvenile detention and probation officers, and city, district, and state court administrators and judges. In addition, juvenile justice systems are not uniform; systems differ by state and can even differ by county within states.

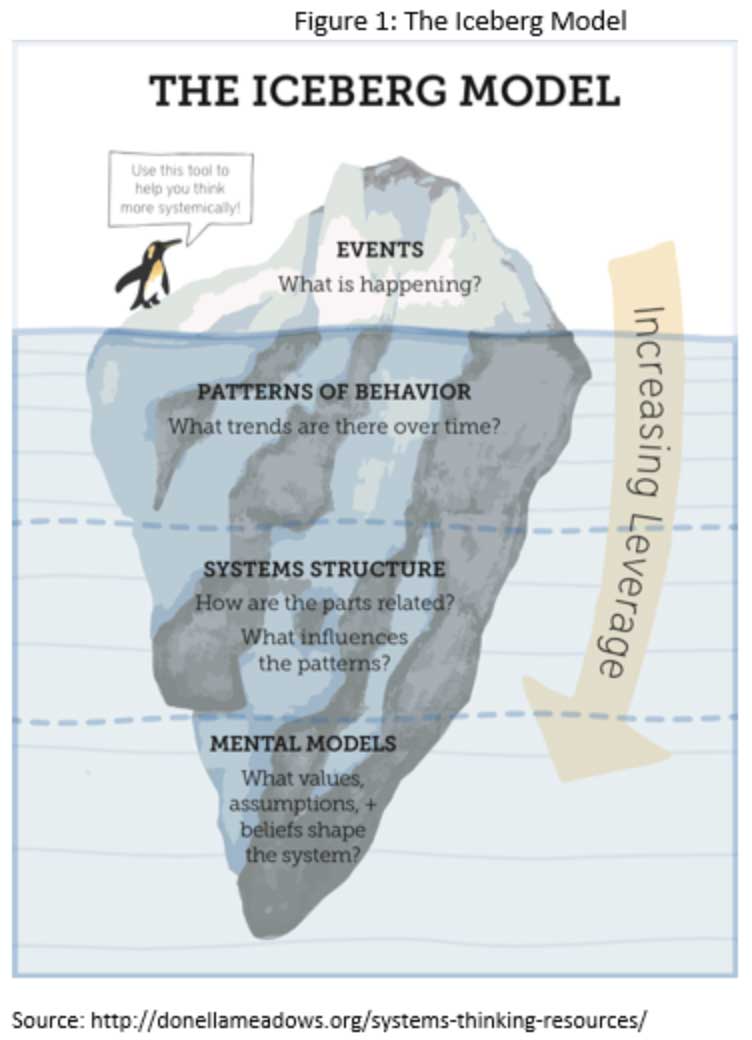

One approach to diagnosing and addressing the complexities of the juvenile justice system is to use systemic thinking to address the root causes of youth incarceration within the system’s multiple levels, applying different perspectives, and mapping the complex interplay of sectors. One helpful systemic thinking technique uses an iceberg metaphor to look beneath the visible events of youth incarceration to see (1) visible events such as youth incarceration, (2) the trends or patterns of activity that produce those visible events, (3) the underlying structures of programs, policies, and practices that produce those patterns or trends, and (4) the mental models or deeply held beliefs that create and reinforce those institutional structures.

The iceberg model metaphor is depicted in Figure 1. It shows that the most powerful and highest leverage elements of a system are the mental models and deep-seated beliefs that provide a conceptual framework for the underlying conditions (institutions, processes, and programs), which, in turn, create patterns of activity that ultimately produce the system’s visible results—the over-incarceration of youth, particularly youth of color. Here is a brief analysis that illustrates some systemic causes of youth incarceration.

Visible events at the tip of the iceberg:

- Over the last three decades, more youth are placed in detention and secure confinement, even as youth arrests have steadily declined.

- Patterns or trends: Many youth start their path to incarceration in school through a school-to-prison pipeline that uses legal mechanisms such as charging children as status offenders for truancy problems or initiating formal juvenile delinquency proceedings as punishment for school discipline problems. Youth of color are much more likely to enter the juvenile justice system, even for minor offenses, through such processes.

- Underlying structures: Policies and practices that contribute to youth entry into the system include posting law enforcement officers in schools to handle discipline and truancy issues; using zero-tolerance policies to punish noncompliance with probation rules, which pushes youth deeper into the system; automatic processing of youth as adult offenders; and the lack of effective assessment and treatment of the estimated 50–80% of youth who enter the juvenile justice system with undiagnosed mental health problems.

- Mental models: Outmoded social norms that see youth as miniature adults with the same level of maturity and culpability as grownups are less likely to support the diversion and provision of alternative community-based services to youth, particularly youth of color.

Solving the problem. One of the greatest levers of transformative change is to “change the mindset or paradigm out of which the system arises.”4 Two key paradigms are operating in this situation. The first is the system’s current understanding of adolescent development: youth are no different than adults and should be treated like them. The second set of beliefs stems from the country’s history of slavery and racial and ethnic bias.

In contrast to the “youth as adults” mindset, research findings from the last two decades of adolescent neuroscience have shown that youth are more likely than adults to not be able to self-regulate their behavior in emotionally charged situations, have higher sensitivity to peer pressure and immediate incentives, and have less ability to consider the long-term consequences of their actions.5 These three factors make youth more likely to engage in risky behaviors such as getting into fights, unruly behavior in class, skipping school, or using drugs and alcohol. These behaviors all increase a youth’s likelihood to catch the attention of school security staff or local police, who are gatekeepers into the local juvenile justice system.

These neuroscience findings are being used to reform the juvenile justice system at multiple levels. At the highest level, in several landmark decisions the United States Supreme Court has referenced the difference in development between youth and adults. For example, the Court’s 2005 Roper v. Simmons decision eliminated the death penalty for crimes committed by youth under age 18. The Court’s 2012 Miller v. Alabama decision held that youth might not be sentenced to mandatory life without parole for an offense committed when the youth was less than 18 years of age.6

Over the last decade, foundations and other institutions have been working at federal, state, and local levels to create a fairer, age-appropriate juvenile justice system. These reforms include:

-

-

- Reforming school discipline practices that criminalize youth for status offenses such as school truancy. An effective reform strategy has been to reframe school discipline as a public health issue, not a public safety issue.

- Diverting youth from entry into the juvenile justice system, especially status offenders and those involved in both the child welfare and juvenile justice systems, by referring them to alternative community-based programs and services.

- Using standardized, evidence-based screening and assessment at intake to identify and treat the previously undiagnosed mental health and substance abuse issues of system-involved youth.

- Increasing youth access and use of juvenile indigent defense attorneys, who are trained to provide effective council to help divert youth from the system or reduce the severity of formal court judgments.

- Preventing youth from being sent automatically to the adult prison system or allowing underage youth (under 18) to be treated as adults by changing juvenile justice rules.

- Creating and enhancing data systems that can monitor, identify, and be used to address racial and ethnic disparities at all points of contact with the juvenile justice system, from intake through aftercare.

-

Other cultural forces outside the juvenile justice system also play a role in creating racial and ethnic disparities in youth incarceration. These biases enable the public to look the other way, allowing treatment for youth of color that would not be tolerated for other groups. This is a much larger phenomenon that touches on deeper issues, including the racial profiling of boys and men of color by the country’s law enforcement system. An extraordinary analysis of this issue has been written by Michelle Alexander in her book The New Jim Crow.7 Fortunately, the issue of racial bias in the justice system is gaining more attention through the Black Lives Matter movement and other national campaigns.

Emerging solutions. One major national juvenile justice initiative that has been working on these issues is the Models for Change (MfC) initiative. MfC was launched by the MacArthur Foundation between 2004 and 2007 in four states (Illinois, Louisiana, Pennsylvania, and Washington) to reform state and local policy and practice. Between 2007 and 2009, MfC launched three action networks, active in 16 states, to (1) address juvenile justice racial and ethnic disparities, (2) meet the mental health needs of youth in the juvenile justice system, and (3) improve the quality of juvenile indigent defense. Between 2012 and 2013, as part of MfC’s Legacy Phase, the MacArthur Foundation invested in a National Resource Center Partnership and partnerships with the U.S. Office of Juvenile Justice and Delinquency Prevention and the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration to secure, sustain, and spread MfC reforms. Community Science is conducting the evaluation of the systemic outcomes and impacts of the MfC Legacy Phase. This evaluation is described in more detail in the program feature article.

1 Chambers, B., and A. Balck. (2014). Because kids are different: Five opportunities for reforming the juvenile justice system. Chicago, IL: MacArthur Foundation: Models for Change Resource Center Partnership.

2 Chambers and Balck (2014), p. 7.

3 Chambers and Balck (2014), p. 7.

4 Meadows, D. (1999). Leverage points: Places to Intervene in a System. Hartland, VT: The Sustainability Institute, p. 17.

5 Chambers and Balck (2014), p. 5–6.

6 Chambers and Balck (2014), p. 5.

7 Alexander, M. (20120. The new Jim Crow. New York: The New Press.