When facing challenges and experiencing conflict, how many times has the thought “If only that manager was fired, then our organization would be able to [fill in the blank]” crossed your mind?

When organizations face internal struggles, it’s natural to look for someone to blame — a so-called villain whose removal, we imagine, will resolve the issue. But time and again, we see that ousting the villain doesn’t solve the problem. Why? Because the broader systemic patterns remain unaddressed. By focusing on the hero-villain dynamic, organizations unintentionally reinforce the very issues they aim to overcome.

As Jackson Lima and Samantha Hardy (Hardy, 2012; Lima, 2023) suggest, this dynamic often arises from an organizational and societal tendency toward either/or thinking — a binary worldview that simplifies complex systems into black-and-white, us-and-them dichotomies. Addressing these patterns enables organizations to pave the way for sustained transformational change.

Let’s explore how to shift this dynamic and build the capacity for meaningful change.

Focus on Systemic Issues and Not A Person

Consider an organization embarking on a transformation journey to address equity. During the initial phase, tension arises around a manager perceived as resistant to change. The team begins to attribute all roadblocks to this individual, believing that replacing them will remove the barriers. The manager resigns, but months later, the same challenges persist: low trust, unclear communication, and fragmented team dynamics. The real problem wasn’t the manager; it was the organization’s entrenched systems and behaviors.

This scenario highlights the critical lesson that focusing on individuals as heroes or villains often obscures deeper systemic issues that must be addressed for sustainable change. Imagine the tension in a room where all eyes are on one person to fix a problem or one person to blame for it. It’s a distraction from the systemic roots that actually need attention.

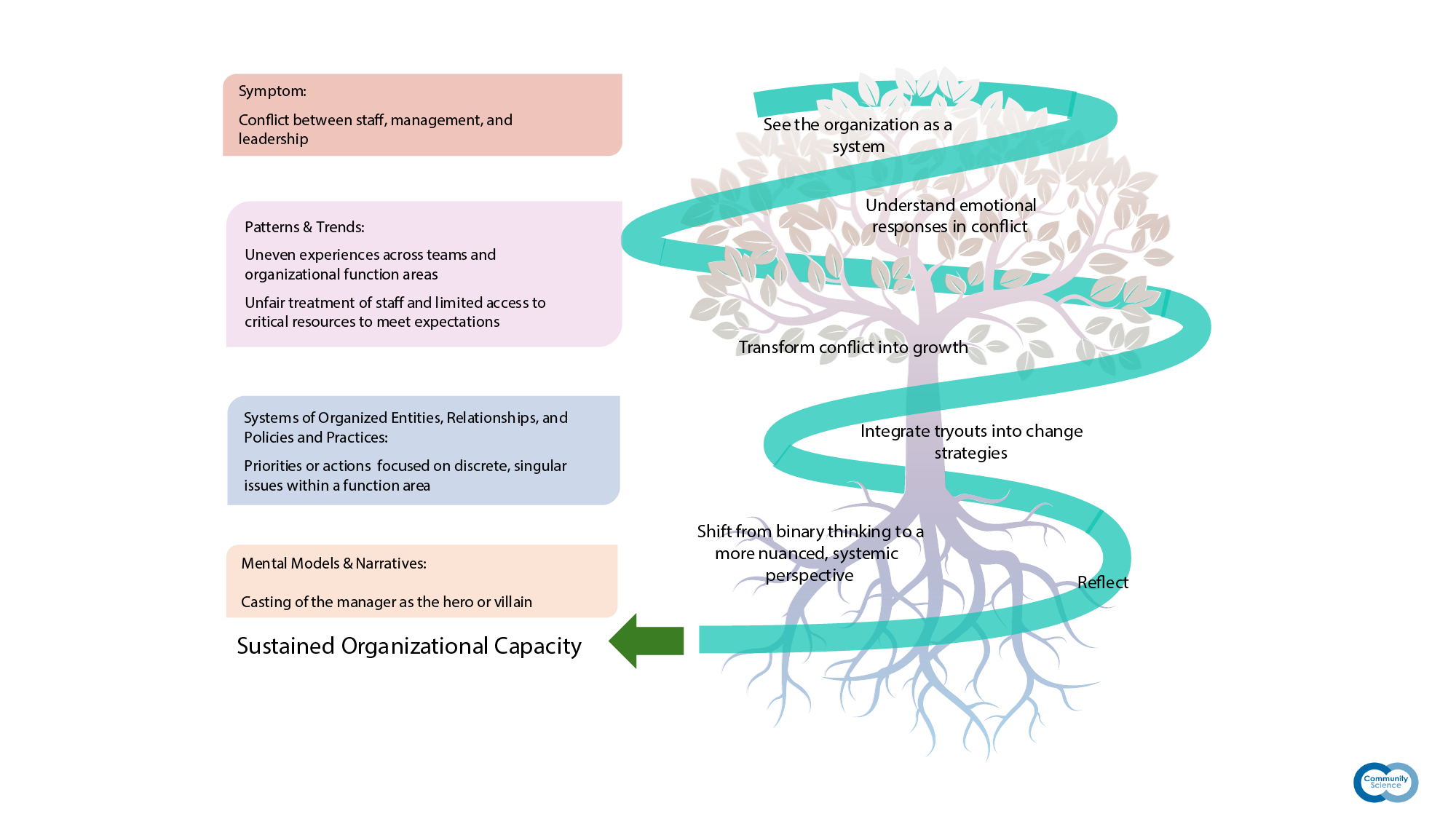

The exhibit here, adapted from the systems tree illustrated in Doing Evaluation in Service of Racial Equity Practice Guide (developed by Community Science and funded by the W.K. Kellogg Foundation), reminds us that organizations are, in and of themselves, complex systems.

Understand Emotional Responses in Conflict

Transformation work often stirs intense emotions, especially when individuals are cast as heroes or villains. These emotional responses, when processed with intention by the persons experiencing them, can serve as a starting point for identifying broader patterns and designing solutions that address systemic issues. The casting of people as a hero or villain can evoke pride, defensiveness, or even despair, but they often sidestep the underlying systemic issues. For instance, systemic issues like unclear communication channels may manifest as individual blame, masking the need for structural improvements. As leaders, it’s important to pause and intentionally process the emotions mentioned above. For example:

- If you feel that you’re viewed as a hero: Acknowledge the affirmation and recognize that the system’s challenges persist beyond individual efforts. Resist becoming the sole solution.

- If you feel that you’re viewed as a villain: Reflect on the feedback. What elements might be valid? Where might systemic patterns be unfairly attributing blame to you?

By processing emotional responses, leaders can approach conflict with greater clarity and purpose. This allows leaders to pause and ask, “What patterns are we perpetuating?” or “How can this moment strengthen our capacity for collaboration?” Such reflection leads to actionable change. Clarity can translate into actionable steps, such as setting clear goals for team dynamics, creating accountability structures, and fostering open dialogue about systemic barriers, and most importantly, moving away from inadvertently and unnecessarily hurting people.

Transform Conflict into Growth

- Recognize the Pattern

- When conflict emerges, pause to identify whether the organization is engaging in hero-villain thinking. Ask:

- Are we oversimplifying the problem by blaming an individual?

- What systemic issues might be contributing to this conflict?

- When conflict emerges, pause to identify whether the organization is engaging in hero-villain thinking. Ask:

- Shift Focus to Systemic Factors

- Move the discussion from individual blame to system-wide reflection. For example:

- Ask: What processes or norms might be making it difficult for everyone to align?

- Don’t ask: Why is this person holding us back by being resistant to the idea?

- Move the discussion from individual blame to system-wide reflection. For example:

- Build Team Capacity for Dialogue

- Facilitate conversations that explore underlying issues. Use prompts like:

- What recurring patterns do we see in how we address conflict?

- How can we create processes that encourage collaboration rather than division?

- Facilitate conversations that explore underlying issues. Use prompts like:

- Experiment with Small Changes

- Start with manageable actions to test new approaches. For instance:

- Implement a team workshop on conflict resolution.

- Introduce a rotating responsibility for leading equity discussions to diversify perspectives.

- Start with manageable actions to test new approaches. For instance:

- Measure and Reflect

- Assess changes in team dynamics, trust, and alignment over time to help you track progress. Share your findings to celebrate wins and refine strategies.

Integrate Tryouts into Change Strategies

As Donella Meadows (Meadows, 1999) highlights, addressing the root causes of systemic patterns is a high-leverage point for transformational change. This requires organizations to embrace a learning mindset and see testing, learning, and adjusting as a core strategy. For example:

- Instead of thinking: This conflict is bad and must be eliminated.

- Reframe as: This conflict is a sign of growth and an opportunity to strengthen our approach.

Small tryouts, such as piloting a new decisionmaking framework or introducing structured feedback loops, can reveal hidden dynamics and spark systemic shifts. Dialogue grounded in curiosity and experimentation fosters collective learning and action.

Shift From Either/Or to Both/And Thinking

Breaking out of the hero-villain dynamic requires a shift from binary thinking to a more nuanced, systemic perspective. For instance:

- Instead of focusing solely on immediate fixes, explore both immediate fixes and long-term strategies that address root causes.

- Replace reactive blame with accountability and proactive capacity building that equips teams to navigate complexity.

Through this mindset, organizations build the resilience needed to sustain transformational change. We unlock our collective capacity to create lasting, equitable transformation when we shift our focus from individuals to systems.

Reflect

Reflection is vital in breaking free from the constraints of binary thinking. To begin your journey, ask yourself:

- Where is either/or thinking showing up in your organization?

- How might we reframe conflicts as opportunities for growth?

- What first step can we take to build “we” capacity?

- What emotions arise in moments of conflict, and how can they guide rather than derail progress?

- What systemic patterns have we overlooked in our responses to organizational challenges?

Transformation doesn’t happen overnight, but each intentional step forward brings us closer to our vision of healthier and stronger organizations that can support thriving communities. By increasing your organization’s sensitivity to either/or thinking and addressing it with actionable steps, the organization is not just responding to conflict — it’s building a foundation for systemic change.

Let’s walk the path together.

Have a challenge? Get in touch with us.

References

Hardy, S. (2012). The Melodrama of Conflict. [Presentation]. Conflict Coaching International.

Lima, J. (2023). Transforming Conflict by Examining Our Stories [Presentation]. Center for Nonviolent Communication.

Meadows, D. (1999). Leverage points: Places to intervene in a system. The Sustainability Institute.

About The Authors

Amber Trout, Ph.D., Senior Associate, has extensive organizational and leadership development, change management, and capacity building experience in the nonprofit and philanthropic sectors. Most recently, she worked with the Institute for Nonprofit Practice to manage the implementation of their new learning agenda, the W.K. Kellogg Foundation to manage the evaluation of the Racial Equity Anchor Collaborative, and the Knight Foundation to map pathways of change and more for an equitable revitalization project.

Suprotik Stotz-Ghosh, MFA, Principal Associate, brings over 20 years of experience in facilitating, building, and evaluating equitable systems, racial equity initiatives for leading multinational nonprofit organizations, philanthropic institutions, philanthropy-serving organizations, and consulting firms. Suprotik oversees the design of equity-centered strategic planning processes for organizations seeking to promote health, economic, and education outcomes.

Jasmine Williams-Washington, Ph.D., Managing Associate, specializes is in the implementation and evaluation of community organizing and organizational capacity building initiatives. Current projects include evaluations and capacity building support for the W.K. Kellogg Foundation, MacArthur Foundation, and Public Welfare Foundation.