Many philanthropic organizations around the country have made it their mission to improve the lives of children and communities of color. Some of these organizations have used community organizing as a means of creating equitable communities by shifting power to those most affected, and strategically placing these individuals at the forefront of the community organizing process. This article discusses some of the foundational principles for promoting equity through the use of community organizing as a strategy.

Community organizing is said to have been started through the work of Saul Alinsky as illustrated in Rules for Radicals, which has since spurred a variety of approaches. National organizations such as PICO, Metro IAF, and the Virginia Organizing Project have become known for their distinct community organizing approaches and work.

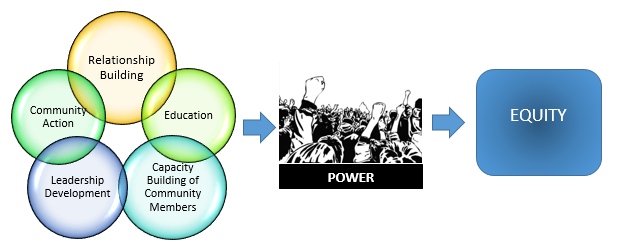

Community organizing is a process that involves (a) developing meaningful relationships and gaining an understanding of community context and conditions, (b) educating community members on an issue, (c) mobilizing community members to take action and create community-level change, and (d) building the capacity of community members to effect systemic change. The ultimate goal is to create an environment where community members hold the power in their communities. Community power means that residents have the influence to acquire the resources and promote the systemic changes needed to improve their environment and conditions. Community power emerges when groups act strategically and collectively (Gold & Simon, 2002). At the base of community organizing are the relationships built by the community organizer with those most affected by the issue who themselves have insufficient power to effect change. The relationship between the community organizer and those most affected by the issue, as well as among the community members most affected by the issue, can be leveraged to increase the community’s power.

Foundational Principles

Of utmost importance are the relationships among the people involved in the organizing process and among the people most affected—across race and class—and the collective consciousness of their common destiny, as well as their linkages with larger institutions and other communities. Though the community organizer’s relationship with those most affected by an issue is crucial, the relationship with the organizer is just one of many critical relationships. The relationship between the community and the leadership of that community, and between the leadership and people who are part of the power structure, are also critical in the process. The process of community organizing essentially involves building relationships among and between residents, stakeholders, and members of the external power structure (e.g., decision makers and public systems) through thoughtful dialogue and collaboration (Ohmer & DeMasi, 2009). The relationships built with those who are most affected facilitate the process of understanding the issues that are more prevalent in the community. Strong relationships broaden accountability for improving communities and strengthening families across economic divides.

Education is the lifeblood of community organizing and capacity building. The education of community members on the issue they identify as most relevant to their situation is crucial to the organizing process. There is power in knowing how to frame the argument but also in understanding the facts that support the change that community members want to see in their community. Education helps galvanize people to take action on an issue and decreases apathy among community members. A community organizer is a critical educator of the community. Paulo Freire’s critical pedagogy involves questioning, naming, reflecting, analyzing, and collectively acting in the world, also defined as a “democratic process of education that takes place in community groups and forms the basis of transformation” (Ledwith, 2005). Freire’s theory is based on the belief that liberation is possible. The more information people have, the more empowered they are to advocate on their own behalf. Freire and others see the process of education creating a critical awareness of larger systemic issues and the possibilities of changing them—a great awareness or consciousness. Education helps community members develop a strategy because community leaders learn to define and frame the issues, how to address them, and their desired outcomes.

The role of leadership, both individual and collective, is key. The prime objective of a good community organizer is to develop community leadership. Identification and development of new leaders within the community is a major outcome of community organizing. However, the leadership of the collective as a whole is most important. Collective leadership means that the community itself has the power to drive the change that is needed. Strong and healthy community leadership expresses the corporate vision and holds itself accountable to the community members. Leadership is a collective process and not just about individuals holding certain positions in a community organization.

Community members must be mobilized to take action on the identified issue. Community power comes from the number of people the community organizer can prompt to take action. The community’s willingness to take action on an issue creates public attention and demonstrates that a large number of people are concerned about an issue that is plaguing their community. This type of community-member-driven mobilization puts pressure on decision makers to be accountable to the community they represent.

Capacity should be built and left in the community. Community organizing should leave both champions and newly identified leaders behind in a community to continue to mobilize the community on future issues. Champions are those individuals who carry a message and push the narrative to the public. Community leaders move the message into action, leading people in the community to move forward in creating the change that community members want to see. In addition to champions and leaders, the community also has the knowledge and tools needed to make decision makers accountable to them. Lastly, community members will have the ability to identify and leverage opportunities for improvement in their community.

The people who are most affected by decisions and policies that create or eliminate the inequities they experience should decide what is essential to address. The community organizer’s role is to responsibly guide—not drive—these people through the process. The use of community organizing as a strategy encourages community members to ask their own questions and enter into that critical sense of thought that will lead to liberation and, ultimately, to an equitable community for all who live there. A community that has the capacity to decide which issues to focus on and act on them by exercising its power is an equitable community.

Because community organizing focuses on systems, foundations and to some extent public funders have been supporting community organizing in some form or shape. Based on Community Science’s experience with the implementation and evaluation of community organizing efforts supported by national and local foundations, we offer the following advice: If there’s going to be change, there’s going to be conflict. Be prepared, or find an alternative to address the change needed.

References

Gold, E., & Simon, E. (2002). Successful community organizing. Chicago, IL: Cross City Campaign for Urban School Reform.

Ledwith, M. (2005). Community development. Portland, OR: Policy Press.

Ohmer, M. L., & DeMasi, K. (2009). Consensus organizing: A community development workbook; A comprehensive guide to designing, implementing, and evaluating community change initiatives. Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE Publications, Inc.