The systems approach to evaluation refers to a theoretical orientation of evaluation practice that draws from systems theory in engineering and other technical sciences (Williams & Imam, 2007). Many evaluators find that principles of dynamic systems apply to the dynamic nature of human behavior and the organizational and social systems that arise from human interactions. Systems approaches to evaluation are being adapted to evaluate everything from small-scale individual programs to large-scale systems change (e.g., entire public health systems or efforts to address global food crises; Patton, 2010). There are many variations of systems approaches, and they differ in which principles are used and how they are applied in practice. The perspective discussed herein represents one of many ways of thinking about and applying systems theory in evaluation.

The Organization

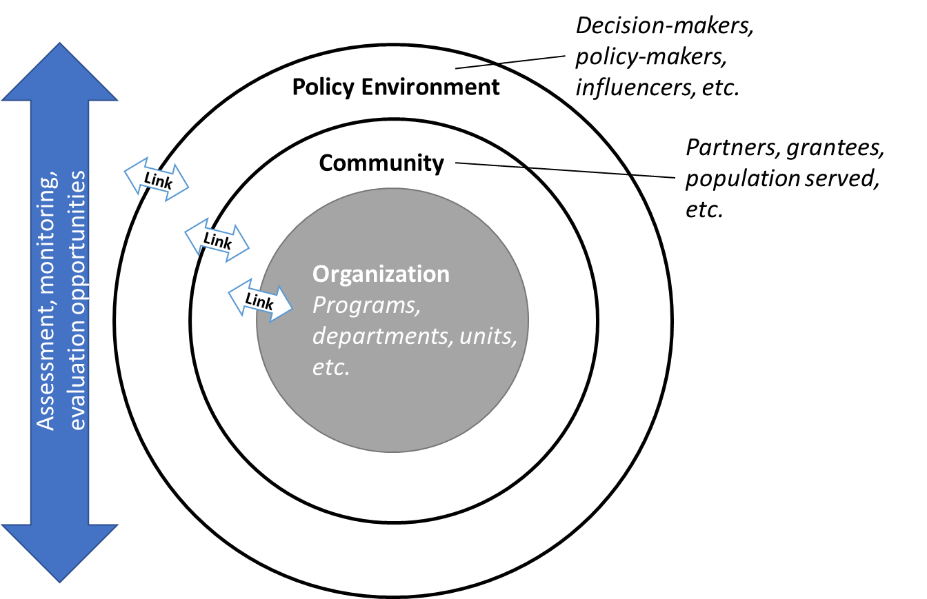

Every organization is embedded in layers of context. Context can include everything from the sociopolitical environment in which an organization operates to the organizational system to which an organization belongs. For instance, an organization can be one clinic within a state health care provider system or even a national health care provider system. The organizational context can also include factors that impact the populations the organization serves, such as the socioeconomic status of its target population. These factors might be called the social context of the organization. Other contextual factors can exist within the organization. These can include its racial/ethnic constitution, gender dynamics, differences in departmental funding, changes in leadership, various elements related to institutional history, and many others. All of these internal and external factors interact with each other to create a complex operational environment that can impact the effectiveness of organizational processes and intended impacts.

Methodology

As is true with most evaluation approaches, the implementation of a systems approach to evaluation follows generally accepted stages and steps of good evaluation practice. Generally, evaluations follow three stages: planning, implementation, and utilization. Within these stages, many of the steps are similar across approaches, such as coming to an agreement about an evaluation’s scope and evaluation questions during the planning phase or collecting data according to the agreed-upon planning during the implementation stage. However, how steps and stages are implemented will vary greatly according to the evaluation theory that guides one’s practice.

In terms of systems approaches, the value added of systems approaches to assessment, monitoring, and evaluation is that the approaches can be very effective at addressing complex organizational environments. A systems approach can be used to help organizations in the following ways:

- By helping the organization choose and prioritize the most relevant environmental factors, the scope of operations is narrowed

- Focus on the links between environmental factors or relational aspects of factors that may impact how the organization operates and their progress toward their goals

- Set up assessment, monitoring, and evaluation systems to effectively guide strategic planning that accounts for the organizational environment

Applying a Systems Theoretical Framework

STEP 1: Due Diligence and Planning: The evaluation of organizations takes place within a complex system of interlinking components. In order to understand these components, one could use a systems approach to conduct due diligence and facilitate organizational alignment. The systems approach consists of the following evaluation activities:

- Conduct document reviews, structured analyses of historically collected data, etc. In a systems approach, a document review and review of existing data takes into account information external to the organization. For example, it may entail conducting a policy analysis (e.g., state/national health care reform policies implemented in the current environment or existing school demographic data for a school system).

- Conduct informal and semiformal interviews with relevant internal and external stakeholders. These interviews will allow the organization to understand how it is perceived, whether the goals of the organization align with environment in which it operates, or if the organization is siloed in any way.

- Helping stakeholders understand the project, outlining the scope of the project, and completing nested models. Nested modeling emphasizes the complexity of interrelated parts of the organizational environment and links them to organizational goals. In most cases, there is an overall governing logic to an organization’s processes and goals that is dictated by policies, leadership, or other factors. This governing structure could be a strategic plan or a standard operating procedures manual. In a systems evaluation, this high-level guidance is graphically depicted as a pathway model that captures the logic of how groups of activities will lead to expected outcomes or impacts for the overall institution. Pathway models are more complex than logic models in that they capture underlying assumptions of which program or organizational activities are expected to lead to which outcomes.

Within this high-level guidance structure, organizations often have additional ideas about how a specific department or program will operate to realize its overall goals. For instance, a department may develop its own strategic or implementation plan in order to meet the expectations of the strategic efforts of the organization. These represent opportunities for nested models within the high-level pathway model.

Taken together, these due diligence steps amount to a systems analysis that helps evaluators determine the appropriate level of focus for the evaluation, assessment, monitoring activities, and type of data collection needed throughout the system or organizational environment. The result is a comprehensive evaluation plan that accounts for stakeholder perspectives across system levels as well as laterally across departments, units, offices, and so forth of the same system level.

STEP 2: Implementation: Several rigorous evaluation and assessment activities are used iteratively throughout the assessment implementation process in order to address goals or needs identified in the due diligence period. For instance, a systems-based evaluation and assessment plan is necessarily rooted in mixed-methods strategies that anchor findings in quantitative data points where possible and provide context with qualitative information gathered directly from stakeholders to supplement and explicate quantitative data. Often variations of evaluation and assessment design and data collection are warranted, depending on the agreed-upon scope of the organizational and evaluation context. This can result in complex multimethod designs that can be a common feature of systems approaches where the methods used to conduct assessments at one level may be different from those needed to conduct assessments at a different level.

Additionally, a systems approach highlights the need for both process and outcome data. Because the interrelated factors that can impact organizational effectiveness can be difficult to untangle, it is eminently important to document that an organization is operating as expected in order to result in predicted impacts or outcomes. Thus, process measures must be collected. Measures of impact, outcomes, or goals are also collected in order to establish temporal contiguity (i.e., processes of an organization are happening at the same time or within the timeframe that makes sense for the expected outcomes).

By drawing attention to system links, a systems approach allows for a close review of how the implementation of a strategy or program design interacts with organizational, contextual, and other factors that lead to desired outcomes. Another feature of a focus on system links is the potential to build in feedback loops for assessment of specific areas of the organizational strategy or program design. Feedback loops are iterations of data analysis and reporting that create opportunities for real-time program decision-making. They allow evaluators to course correct if necessary or evaluate the path in which a program or strategy is moving. This is also an opportunity to adapt components of the program or organizational system if factors in the implementation context have changed. These opportunities keep a program or organization relevant in the dynamic and changing environments in which they operate. Thus, the systems approach promotes the adaptation and survival of programs and organizations.

Examples of appropriate data-collection strategies include the following:

- Conducting informal and semiformal interviews

- Creating and implementing questionnaires of varying types for different stakeholder audiences

- Creating and implement tracking systems of various processes, projects, and programs

- Conducting site visits for training and observation

- Inventorying and leveraging existing institutional data as well as external public data sources

Results and Conclusions

The full-scale implementation of outcome assessment and evaluation often consists of several phases rolled out over time. The process can appear repetitive as opportunities for refinements are identified, operations adjusted, and factors retested or assessed. In long-term evaluations, systems approaches can be lengthy or time consuming as the assessment scope grows year over year and additional factors are incorporated. The key to keeping client focus and engagement is to consistently report on findings in meaningful ways that result in organizational improvement. For example, this can be done by adding elements of rapid-cycle evaluation for factors that lend themselves to expedited collection, analysis, and reporting (one form of feedback loop) in conjunction with traditional, in-depth, timely reporting cycles.

It is also important to manage expectations throughout the process. Changing entire systems such as public health systems or school systems takes time, and therefore findings from assessments and evaluations of systems changes in the short term cannot always tell the story of change. Additionally, some data collection and analysis may not be able to occur until the system has had time to change. This can lead to the appearance of null findings in the short term and can lead to frustration and concern in clients. It is important that the research team take clients on the journey with them through timely, iterative communication. As mentioned previously, making shorter-term reporting meaningful for program or organizational improvement on the way to overall outcome determinations is very important.

Conclusions

Planning large-scale assessment, monitoring, and evaluation across various levels and components of an organizational system is best addressed by using a theoretically positioned methodology that helps evaluators grasp the complexity of an organization in context. In order to be successful with this approach, begin by completing due diligence—including thorough, structured document reviews; semiformal stakeholder interviews; and facilitated nested modeling. The research team should draw from mixed-methods approaches to document operational processes and impacts or outcomes to which those operations may contribute. Most importantly, evaluators should accept the complexity that the process itself engenders and the length of time or effort entailed in using a systems approach with a client by keeping the client engaged and utilizing reporting methods that demonstrate progress and value.

References

Lavinghouze, S.R. (2006). Practical program evaluation: assessing and improving planning, implementation, and effectiveness [book review] 3(1):A25. Available from: URL:http://www.cdc.gov/pcd/issues/2006/jan/05_0121.htm.

Patton, M. Q. (2010). Developmental evaluation: Applying complexity concepts to enhance innovation and use. New York, NY: Guilford Press. For an example of small-scale implementation, see Trochim, W., Urban, J. B., Hargraves, M., Hebbard, C., Buckley, J., Archibald, T., & Burgermaster, M. (2012). The guide to the systems evaluation protocol. Ithaca, NY: Cornell Digital Print Services.

Williams, B., & Imam, I. (2007). Systems concepts in evaluation: An expert anthology. Point Reyes, CA: EdgePress of Inverness.